The Difference between Education Theory and Practice

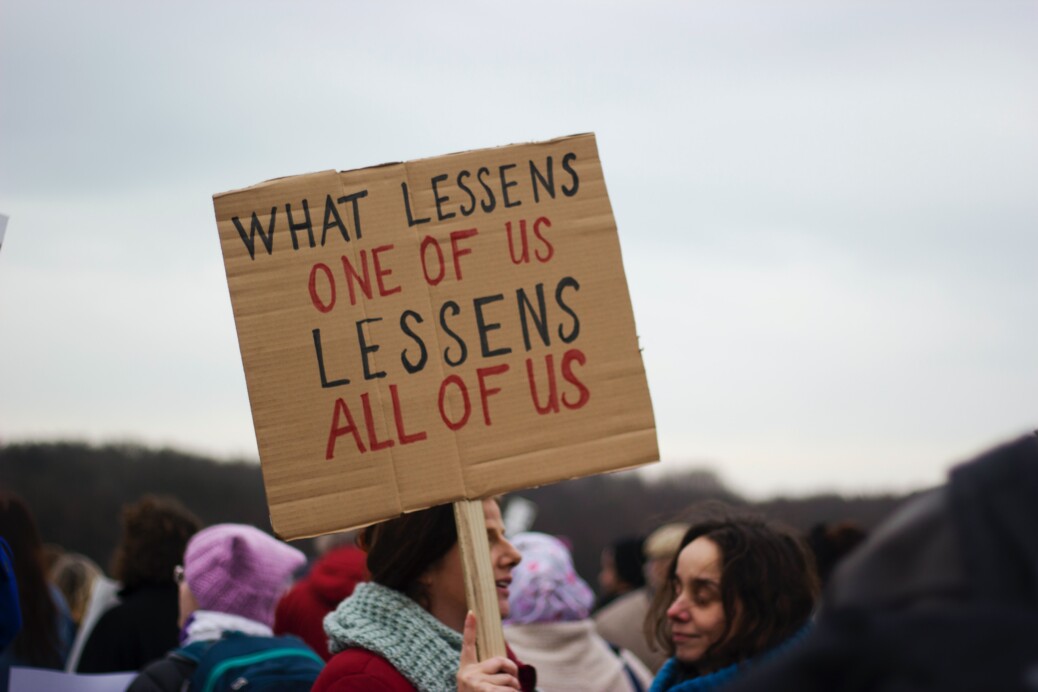

When someone asks about the work I do, I quickly explain how Go Together works with schools and communities to promote equity in education. I am often met with skepticism rather than excitement. “But education equalizes everyone,” they protest, “Education is already the most equitable tool we have.” I agree that education can be a powerful tool for creating a better society. What my friends’ perspectives miss, however, is the difference between this American education theory and its practice.

Indeed, scholars like Horace Mann have long sung the praises of our system, calling it “beyond all other divides of human origin…a great equalizer of conditions of men – the balance wheel of the social machinery.” Gerardo Gonzalez, writing 153 years after Mann, adds that “Education is the great equalizer in a democratic society, and if people are not given access to a quality education, then what we are doing is creating an underclass of people.”[i]

This is the idea of American education to which my friends refer. In reality, our system has strayed from this goal throughout history and continues to do so today. Ever since its founding, American education has been used to erase native cultures, to otherize racial and ethnic minorities, to discipline non-normative bodies and minds, and to punish poverty. For example, consider native assimilation, segregation, lack of disability accommodations, and under resourced low-income schools.

Native American Assimilation in American Education

Upon arriving in North America, European colonists were met by native peoples. At first, native Americans taught colonists survival techniques. For example, natives taught colonists to identify edible plants and new farming techniques.[ii] Their relationship quickly turned to violence and exploitation, however, as colonists sought economic and social domination over the perceived “savage” cultures. This perception was so pervasive that it was included in the Declaration of Independence. The founders called natives “merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”[iii] Following the Revolutionary War, the federal government formed over 400 treaties with native peoples in which natives surrendered land in return for services – including education.[iv]

The resulting education of the so-called “Indian Savage” can be summarized in one word: Assimilation. New education initiatives mirrored missionary schools of the early 1600s. Such schools removed “Indians from their tribal and family members, religion, language, and homeland” to “learn non-Indian ways.”[v] The schools worked to erase native culture and assimilate the students into white society. Since then, these strategies shifted into public schools as integration became the favored method for degrading Indian ethnic identity. Today, these assimilationist attitudes remain prevalent in curriculum, practices, staff attitudes, and school environments.[vi]

Segregation

Ever since the beginning of race-based slavery in North America, Black people have been perceived as somehow inferior to whites due to race alone. Slaves were denied all rights, including the right to formal education, even through emancipation in 1863, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Black education was further limited by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling which cemented “separate but equal” as the law of American education. In reality, separate but equal intentionally disadvantaged the Black community. It allowed for unequal funding for Black schools, drained the Black economy, limited opportunity even further, and traumatized generations of Black Americans.[viii]

Though Brown v. Board of Education repealed separate but equal in 1954, the resulting social uproar delayed integration for years. By 1966, “two-thirds of Black students attended schools that were 90 to 100 percent Black; 80 percent of white students attended schools that were 90 to 100 percent white.[ix] Busing, white flight, housing segregation, hostility toward Black teachers, and more issues plagued Black education. In comparison, today’s racial segregation is the same as it was in 1980.[x] Additionally, Black students’ academic performances are between 0.5 and 0.9 standard deviations lower than their white counterparts.[xi]Poverty accounts for some of this relationship, but it is clear that racial segregation and its harms are alive and well in today’s education system.[xii]

Modernizing Our Conversation

The histories of assimilation and segregation demonstrate that our country has a storied history of marginalizing minority communities since its founding. Such marginalization has tangible effects on student learning, economic mobility, and individual well-being. Further, we must realize that this phenomenon is not limited to our past. Modern students suffer the consequences of institutional inequities in education just as previous generations have. For example, one may consider racial zoning, racial biases in course tracking, school choice, resource distribution, transportation, accessibility, standardized testing, financial costs of higher education, and more.

Throughout the next month or so, I will expand this conversation with a weekly deep dive into modern educational equity problems. I will highlight the specific issue, give examples and background, discuss implications, and suggest solutions that center equity as a foundational goal.

Overall, our education system promotes inequity on a macro level. However, this is not to say the system is entirely irredeemable. Individual schools and programs have created positive change and continue to do so today. For example, they provide meals and childcare, employ millions of people, and empower entire generations to participate in society and create positive change. To clarify, my point is not that education is bad. Rather, I argue that our practice does not always live up to the ideals that Mann, Gonzalez, and others have shared. Education can be a powerful tool to create a great and good society. In order to get there, though, we must contextualize it in historic harms, deconstruct problematic systems, and center equity. Only then can we bridge the gap between theory and practice.

[i] Growe and Montgomery, 2003

[ii] Carson, 2006

[iii] Jefferson et. al, 1776

[iv] Deyhle and Swisher, 1997

[v] Deyhle and Swisher, 1997, p. 114

[vi] Deyhle and Swisher, 1997, p.115

[vii] Editor, 2014

[viii] Ramsey, n.d.

[ix] Reardon, 2016

[x] Startz, 2020

[xi] Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis, n.d.

[xii] Reardon, 2016

Works Cited

Deyhle, D., & Swisher, K. (1997). Research in American Indian and Alaska Native Education: From Assimilation to Self-Determination. Review of Research in Education, 22, 113-194. doi:10.2307/1167375

Editor, N. (2014). Brown at 60 and Milliken at 40. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/ed/14/06/brown-60-milliken-40.

Growe, R., & Montgomery, P. S. (2003). Educational equity in America: Is education the great equalizer? The Professional Educator, 25(2), 23–29.

Jefferson, T., Franklin, B., Adams, J., Sherman, R., & Livingston, R. R., National Archives (1776). https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

Ramsey, S. (n.d.). The troubled history of American education after the Brown decision. The Organization of American Historians. https://www.oah.org/tah/issues/2017/february/the-troubled-history-of-american-education-after-the-brown-decision/.

Reardon, S. F. (2016). School segregation and racial academic achievement gaps. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(5), 34–57. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.7758/rsf.2016.2.5.03.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Ftest&refreqid=fastly-default%3A19504f492545914f301e7b2b2d9cb59d.

Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis. (n.d.). Racial and ethnic achievement gaps. The Educational Opportunity Monitoring Project: Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gaps. https://cepa.stanford.edu/educational-opportunity-monitoring-project/achievement-gaps/race/.

Startz, D. (2020, January 20). The achievement gap in education: Racial segregation versus segregation by poverty. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2020/01/20/the-achievement-gap-in-education-racial-segregation-versus-segregation-by-poverty/.